The Look of a Liturgical Bell

|

|

An obvious question: how does it look on the outside?

Is it beautiful? A liturgical instrument should be fit for liturgical use. The shape of the bell is dictated by acoustic considerations; except for some modern, experimental bells, any bell that deviates from the classic lines will not sound good at all. Russian-style bells also usually have iconography and inscriptions on them. What is the quality of these? Are they real examples of the iconographer's art, or do they look crude and inelegant? Your own sense of tradition and good taste will be the judge here.

General type and characteristics of profile

In general, what kind of bell is it? Navy bells or railroad bells were

made just to make a loud clang! either to warn or to announce. They were

not made to sing, and they don't.

Are the walls of the bell of uniform thickness throughout? Your bell was

stamped from a die or turned on a lathe. There will be nothing musical

about it.

Cast iron school or church bells like those that were sold through the Sears catalogue at the turn of the century don't sound much better. They were designed to be heard (and to be inexpensive), not to be members of a choir. Iron is much cheaper than bronze, but quality bell makers don't use it.

Cast iron is for bathtubs.

But are old acetylene cylinders really adequate to the worship of God?

Yet one monastery bangs on an old engine block to announce the divine services.

Icon and Ornament:

Does the bell qualify as a 'singing icon'?

|

|

Centuries-old tradition encircles a bell with bands of ornamentation,

lettering, and icons.

Apart from the voice of the bell itself, this iconographic and scriptural

art is what makes a bell into a liturgical instrument.

Icons and ornamentation should be cast with the bell itself, not incised

afterwards. Except in very large bells, it should be no more than 1.5

to 2 millimeters higher than the surface of the bell. Ignoring either

of these rules will aversely affect the sound.

The iconography itself should be crisp, clean, and clear.

Icons and lettering should be as precise as the famous iconographic bronze work of the 19th century. Eyes and fingers, folds of the clothing, details of emblems, the faces of the saints— all should be distinct, like the fine brushwork on a painted icon.

Physical configuration and technical dimensions

Of course, you can't evaluate everything there is to know about a bell's physical configuration with a quick glance at its profile, but you should at least know the basic principles of campanological geometry, so here are a few rules of thumb.

|

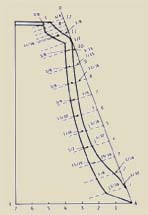

The profile shown here— that of a bell from the last century by N. I. Olovyanishkov— is not too distinct from that of a non-Russian bell, so regardless of the bell you are looking at, the same basic principles will apply.

The diameter of a bell's lower part, its "skirt," should be exactly twice the size of its upper diameter.

Its height, not counting the crown, should be somewhere near 4/5 its lower diameter.

The thickness of the wall below the zone struck by the clapper should be no more than 1/10, and no less than 1/14, the diameter.

The upper wall of the bell should be three times smaller than the lower.

The clapper, or "tongue" of the bell should weigh 1/20 the weight of the bell. It should be made from forged, soft, riveted steel.

Inscribing your bell with fitting words

Sometime around the year 535, the Carthaginian deacon Fulgentius Ferrandus sent a bell to his friend Eugippius, abbot of a monastery near Naples.

The letter he wrote to accompany his gift is the earliest reference we have to a bell used to call Christians to worship, though of course the very fact that he was sending a bell tells us that bells were already in use, at least in North Africa, before then.

Fulgentius had an interesting thing to say about inscriptions:

"I have not permitted my name to be inscribed on it because the Holy Spirit has already written it on your heart."

We at Blagovest believe that, as liturgical instruments, bells should glorify God, and not man. Therefore, like the deacon Fulgentius, we encourage you to inscribe your bells with liturgical texts rather than with the names of donors or even of deceased persons. Of course, donors often request the icons of their heavenly Protectors, and God is glorified in his saints— and will surely glorify those who glorify him! And sometimes the inscriptions ask for prayers for the donors or their loved ones, as well.

You can inscribe the bell in any language (we've even ordered Arabic!) The only limitation is the length of the inscription, which varies, of course, by the diameter of the bell.